Is ordinariness the new fantasy?

And yet there are enough current and forthcoming games that draw at least part of their inspiration from the everyday that one could make an argument for such a case. Take Life is Strange with its high school melodrama (er, and time travel), Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture and its meticulously realised 1980s British villages (er, and space ghost apocalypse), or the wilderness and human isolation of Campo Santo’s Firewatch (er, and… littering?).

These are three examples which admittedly took a few minutes to come up with, so clearly “ordinariness is the new fantasy” would be a bad argument to make. However, as a short intro to a review, it’ll do the job*.

Home is Where One Starts is the creation of David Wehle; to the best of my knowledge it’s his first release and is available for a few quid on Steam or itch.io. Its an exploratory game, demanding more in the way of thought and introspection than reaction times and physical skill. Oh, I may as well stop dancing around the hateful term: it’s a ‘walking simulator’, all right?

The game puts you in the tiny shoes of a young girl; age not specified but young enough to be a kid, old enough to deconstruct computers and start highlighting passages in the Bible. Make of that what you will. You explore this young girl’s memories of her childhood home, a trailer in a rural setting, with narration from her adult self occasionally interspersed when you encounter key memories. Wander, explore, see what you find. Eventually the narrator will drop in a particular comment that lets you know where to go if you’re done exploring and want to progress her tale.

This is a short and, superficially, simple game. Assuming you follow the narrator’s hint when it arrives, a playthrough will wrap in under half an hour. This isn’t a linear game, though, so there’ll be more to go and find should you so wish.

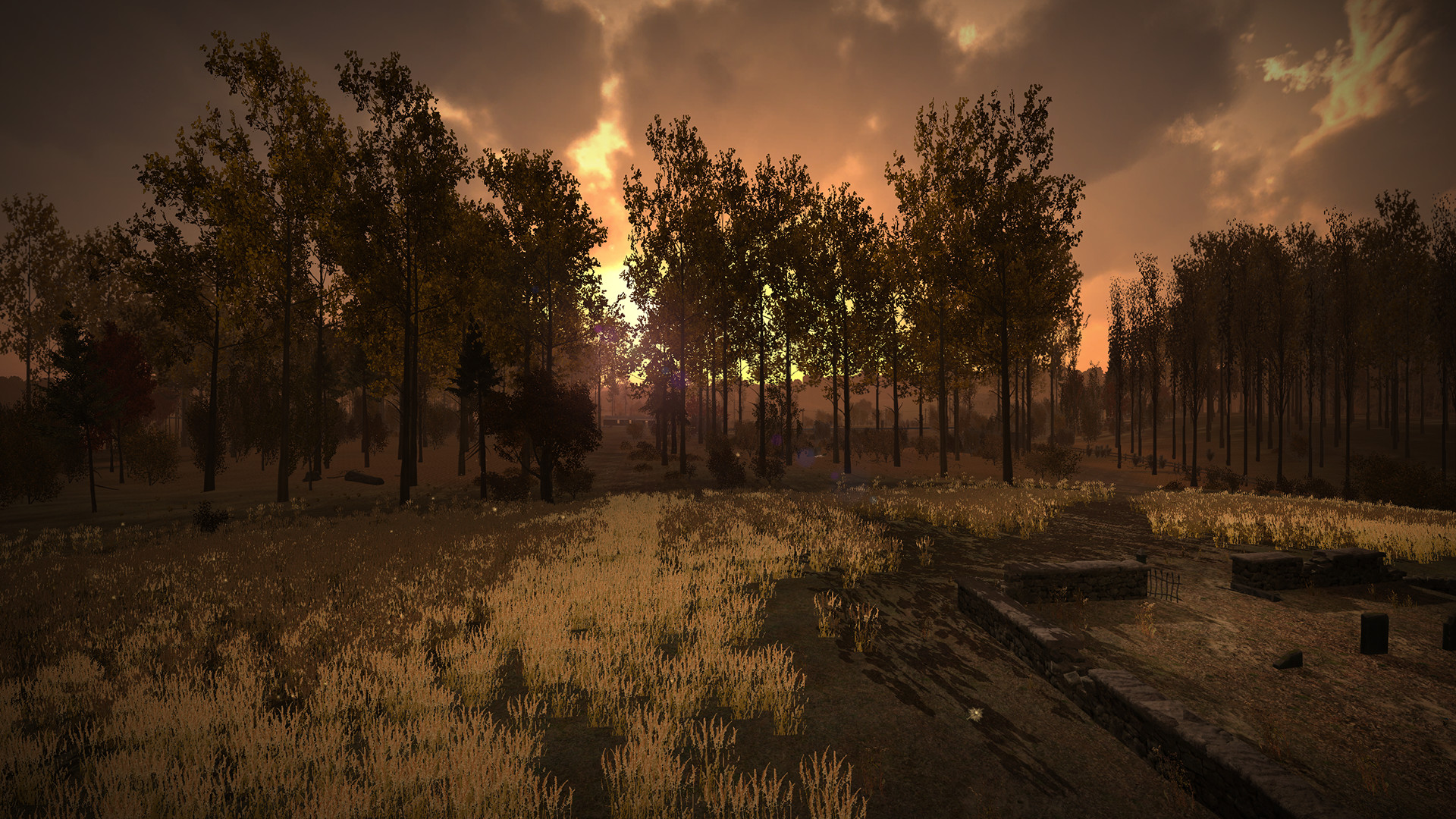

Among the greatest strengths of Home is Where One Starts is its environmental design, which provides a lovely environment to explore. The use of colour is excellent; the palette is a warm assortment of yellow, orange and brown tones, a strong evocation of the countryside in Autumn. The rising sun lends the environment an additional warmth and homeliness that is absent from the childhood home itself.

The minimalistic sound design complements this with the sounds of long grass in the breeze, trees rustling and birds calling all counterposed to the stark silence inside the trailer. The soundtrack, too, is restrained, low key and ever so slightly melancholic. These visual and auditory elements come together to evoke a sense of nostalgia – for a place I’ve never been.

This success is important, because Home is Where One Starts is all about very ordinary experiences. Fishing by a pond. Climbing a giant hay bale. Watching the neighbour’s dog through a fence. Finding a child’s fort in the woods. These are all very grounded, down to earth moments, and although the specifics of these fictional memories won’t resonate with everyone, surely the significance of them will – particularly those who found home suffocating, who wished to escape, or who simply took pleasure in small things.

Given all this, Gone Home is an obvious reference point, despite that game’s attempt to trick players by setting up misleading expectations. The key difference here is that this is open-ended exploration with a timer running in the background, rather than a largely linear narrative experience with mild puzzling. Or looked at from a narrative perspective: Gone Home tells the stories of an entire family, with both their interior lives and their relationships with each other illuminated by anecdotal evidence. Home is Where One Starts focuses entirely on its narrator; the little girl as an adult reflecting back on a pivotal day in her life; it is all about her experiences. We see fragments of the lives of others but that is all: a photograph of a mother and her daughter, the father’s face torn away. Of the father, who at this time remained a presence in his daughter’s life unlike her absent mother, we see only his alcoholism, his love of hunting and fishing, and an interest in war (thanks to a novel, The Middle Parts of Fortune, and what looks like a Civil War painting, both in his bedroom).

This story as a game, or game to tell a story, won’t be for everyone. And I don’t mention this as the usual “ah, it is a walking simulator” get-out clause**. No, it’s because this is a story that is about ordinariness. As I trudged through the game’s attractive but largely empty landscapes I wondered about the game’s use of negative space, that technique in visual art of drawing attention to what is present through the use of what is not; the equivalent in storytelling is letting the reader’s imagination seize on subtle implications and leave them to do the heavy lifting themselves. Home is Where One Starts uses these techniques well; the ambient noise of rural environments between its small pieces of narration, its sparse nuggets of personal history and memory. The gaps it leaves you fill in for yourself, speculating and imagining what the narrator’s life was like, or ruminating on your own childhood.

I found myself reflecting on my childhood in rural Yorkshire, surrounded by acres and acres of crops, exploring old farmyards full of rusty, abandoned machinery I was warned away from, and watching combine harvesters churn through wheat. I had a sister, so wasn’t an only child. I was far from friends, but had loving parents. I lived in an old farmhouse, and not a trailer (except for six months while some work was being done, come to think of it). I mention all this to emphasise that my childhood was different from that of the narrator, but I found myself pondering commonalities, ruminating on my own past, and remembering the moments when I too learned to understand the invisible walls in my life***.

So Home Is Where One Starts is a nice, clever meditative game. It encourages reflective thought and imagination, which really is what such stories as this are about.

That said, even understood on its own level it’s not without flaws. For all that its environments are attractive, they can never be a patch on exploring a real pocket of nature, Oculus Rift support or not. Of course, nature won’t convey an authored story to you either, not unless Mother Nature and the Green Knight get together for a book club. And attractive or not, despite the small explorable area you will run into repeated objects and textures: the same overdue bill notices, the same newspaper pages, etcetera. Maybe I only noticed that because I’m obsessed with looking at garbage. Who can say?****

Given the brevity of Home is Where One Starts, I’d also be remiss to not admit that my initial experience felt underwhelming. While exploring the trailer seemed an obvious first step, neither the narrative nor the environment suggested where I should look subsequently. Instead I began walking toward landmarks I could see, wondering if I was missing something, or if the game had failed to convey some sense of direction. Later I realised that the explorable area is quite small, and each landmark is mostly positioned such that you can spot one or two others (the trailers’ windows being good for this), with only a few being notably well-hidden.

It is also a shame that you need to turn to the Steam achievement system in order to understand whether or not you have ‘seen it all’. Of course, many will simply play this game once, but it’s short enough that repeating it to try and absorb a fuller story is hardly unlikely. If you do find everything in one sitting (including revisiting what you’ve already seen) then there’s a slight change in the outro sequence, but it’s abrupt enough that you’d be forgiven for being confused by it. Otherwise, to know what you may have missed, it’s checking the achievement list for you, bucko.

Still, these criticisms ultimately fell away, for me, after spending an hour and a half running through Home is Where One Starts three times. Once I’d given up on my urge to establish the ‘correct path’, to shove a bit into the mouth of the metaphorical horse that is narrative drive, and had instead settled into simply ambling and exploring, the game’s charms came through. They’re as much what’s deliberately not there as what is, and that’s a clever and apt technique for a game that encourages self-reflection.

And hey, look at that, I’ve not tried to quote Eliot or Steinbeck even once.

* At this point I had already rejected an intro that drew comparisons with American landscape painting, another that was just more mumbling about “walking simulators”, which the world probably doesn’t need.

** That’s largely just an excuse for people with little patience to rag on things they lack the patience for. Lots of people don’t like Diablo-style action RPGs, but writing about those isn’t bundled with pre-emptive apologies, is it?

*** This may be a metaphor. I suppose you’ll have to play the game and find out for yourself.

**** The police, obviously. Please don’t rat me out.

Here’s me playing through the first bit of the game if you want a taster for what it’s like to explore its environments. I’m sure you can tell a lot about a person from the way their gaze lingers, hmm?

Comments

2 responses to “Home is Where One Starts is what you make of it”

I feel every article about Diablo should start with a pre-emptive apology.

Also, would you say, given that you played it three times that this game might fall into the Toybox genre (coined by Harbour Master) rather than Walking Simulator?

Really liked the write up and it became immediately nostalgic for walking around the countryside in Portugal, being young and bored. Mind you, Limbo also makes me flash back to my youth in Portugal for the same reasons.

I considered using the term “secret box” again, but in the end I decided to run with the more widely recognised term. I’m not sure if I agree with that decision now…

For anyone reading this not familiar with “secret box”, it originates here:

http://www.electrondance.com/screw-your-walking-simulators/

And the quick definition is: “A secret box is a game which is built around some form of content and challenge is trivial or absent. The emphasis is on conveying moments or ideas to the player rather than testing the player’s abilities.”

Glad you liked the write-up! I’m a bit worried about your childhood though if Limbo reminds you of it. ;)