There’s a vibe to Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP that few games have achieved: a mix of ironic detachment, genuine cool and postmodernity. It is, to pick on the internet’s current punchbag of choice, exceedingly hipster – what a self-described hip individual might aim for, at any rate. It’s smart, slick and achingly referential but waves this aside, insisting on not taking itself too seriously. Take a gander at the game’s description on its website:

“If you have not already done so it is essential that you undergo the AUDIENCE CALIBRATION PROCEDURE (included above), a brief but essential audiovisual introduction to Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP aka one of Time Magazine’s ‘Top 10 Videogames of 2011’ aka that cult classic prog rock videogame record with an album’s worth of music from maestro Jim Guthrie aka the prequel to John Madden’s Battle for Middle-Earth aka The Thrillmarillion aka another fine videogame from the wizards at Capy aka the very first videogame project to emerge from the art, design & research team at Superbrothers Inc. aka a little project made by a tiny team in Toronto, Canada aka now we are cosmic friends forever, ok?”

I mean. You know. I think it’s cool, but I can imagine people reading that and thinking it’s the biggest load of tosh they’ve seen in weeks. Yeah?

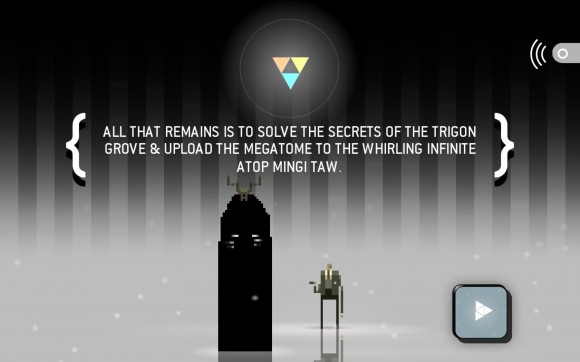

Okay, okay, enough of that. Let’s take a different tack. From my first moments with the game I felt charmed, because it’s a delight to experience. The graphical style is redolent of the 8- and 16-bit eras without being slavish in its reproduction; it’s a stylistic interpretation of those old technological limitations. The animation is similarly wonderful right down to details like the way a stag disappears into the undergrowth when startled.

Sound and music, too, are excellently integrated. Jim Guthrie’s soundtrack is superb – happily, the whole thing is available free to Steam players or Humble Bundle purchasers – and maps itself quite organically to the game’s scenes, growing into intense swells at moments of heightened drama or accomplishment before ebbing into the background so that the rest of the game isn’t smothered by it. Sound effects are sparing but lush and well-matched to what’s happening onscreen at any given time. Favourites here include the skeletal warriors bashing on their shields – an echoing bass boom that sounds suitably warlike – and the sound of the player character donning or removing her pack (a rummaging effect that feels organic and homely).

Listen, I don’t often go on about sound effects in games. Indulge me. This game is really rather lovely.

Still, it’s not all roses. What I’ve not yet mentioned is my first thought about Sword & Sworcery: that it seemed like a (very lovingly constructed) portfolio for the developers’ art and music. The game’s introductory narration explains that there are four Sessions of which the first is a tutorial; I raised an eyebrow at a quarter of the game being a tutorial and raised the other when I spent that tutorial doing not much more than clicking on things I was told to click on. I didn’t mind too much, since I was enjoying the aesthetics so much, but it seemed dreadfully limited. A few friends have given the game up after the tutorial on the assumption it didn’t have much more to offer. That’s a shame, as it really does. You’re drip-fed new challenges as you progress, both in terms of combat and puzzles.

Combat revolves around selecting icons for a sword and a shield at the correct moment; it’s all about timing. There are visual and auditory cues for what an enemy is about to do and your actions are essentially all reactive. It can be a little rote – there are four enemy types throughout the game and the two of those which offer a challenge appear three times and once respectively – but the penalty should you fuck up a pattern is suitably harsh. These sequences are well done as defeat or injury never feels like the game being unfair, only the player falling short of what was demanded. A further nice touch is that the game reduces the number of life points you have each time you clear a major objective (one of many nods toward classic action adventures like The Legend of Zelda). As your safety net shrinks your reactions and memory must improve: it’s a balance that works.

Most of the game’s puzzles are point and click affairs but they eschew inventory juggling and dialogue trees in favour of experiments in environmental interaction. Each puzzle tends to be somewhat unique and they are all clearly inspired by the tactile possibilities of touchscreen devices, though it’s perfectly possible to play with the mouse. I don’t want to spoil any of the puzzles for you so I’ll simply advise you remember all of the basic lessons the game teaches you and be prepared to experiment. If you are stuck it’s usually because you’ve forgotten something, not because the game is being an arse. You may find yourself clicking and dragging your mouse/finger over everything at points, but when you hit upon the solution you’ll probably be kicking yourself. Mousing yourself. Fingering yo-

So that’s the mechanical and surface aesthetic stuff. There’s more going on here. The game presents itself in an unusual way with a focus on its archetypal/mythic elements. Hell, the game’s narrator is literally named The Archetype – a cigar-chomping chap in a suit and tie who knows quite a bit about what’s going on. On the other hand its protagonist, The Scythian, is a wandering warrior woman questing to defeat an ancient evil called the Gogolithic Mass. Why the Scythian? God knows; maybe because they appear in Conan a bit and have a cooler name than Cimmerians. Why the Gogolithic Mass? Again, no idea; it also sounds cool and “lithic” means something to do with stone, but I’m fairly sure this is not the ancient demon spirit of Stone Age go-go dancers. Still, the characters are themselves archetypal: the questing warrior without a name, the ancient and incomprehensible evil. The game’s supporting cast include Logfella, a lumberjack, the Girl, his girl, and Dogfella, the Scythian’s loyal dog.

The game runs and plays with these archetypal elements, balancing its characters on a knife-edge between ignorance and awareness of their roles. Most of the dialogue is knowing and ironic to the point of absurdity. This tendency also emerges via an ability the player gains after the tutorial: looking for tips or tidbits of information and humour via a mind-reading book, which presents the internal monologue of the game’s five friendly characters as a series of tweets. “I must’ve nodded off during The Scythian’s super epic story,” thinks Logfella. “I have a really low tolerance for lore.”

The fourth wall is casually and regularly broken throughout. Since this is also implicit in the way the player interacts with the environment – in a way the player character never could – it’s actually rather refreshing to see dialogue that uses the second person, commentary that directly references the player, or characters commenting on the overt game-ness of what’s happening around them.

If the game’s postmodernity is clear as day its themes are a little trickier to unpick. There’s a folkloric aspect to the way it plays with myth (a lumberjack and his wife? A nameless wanderer? Inevitable tragedy? C’mon!). The game doesn’t clearly set out to say anything in particular, however, unlike most fairy tales or myths. Perhaps the intention was a simple subversion of the triumphalism typical of fantasy videogames, particularly the iconic titles Superbrothers most obviously tips their hats to. If so that isn’t a particularly pointed critique, but then ambiguity always has been more memorable than the explicit.

I am not, however, convinced that there is more to what the game is saying than this. It’s a charmingly presented package but I think its depth is a ruse generated, intentionally or not, by its referential, ironic and mythic presentation. If anything that’s a problem with the concept of post-modernity: that in acknowledging there’s no truth it’s necessary to admit there’s nothing to say, and therefore nothing must be said in a spectacular way.

One could argue that the game is intended satirically and that, in overtly evading meaning whilst subverting the fantasy and gaming traditions it invokes, it’s intended to make a point about how videogames have very little to say in a narrativist manner. This has occurred to me but I’m always suspicious of what appears to be an empty cypher, as so often that is what they turn out to be.

Ultimately, though, all of this wank hat material is down to the player’s own interpretation, and agreeing or disagreeing with it does not detract from a rather fine shortform game; a quickly digestible novelette with a lot to distinguish itself. And did I mention that the sound and visuals are absolutely gorgeous?

Comments

6 responses to “Review: Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP”

There are some lovely touches throughout, including The Archetype's declaration that it was time to sacrifice The Scythian, acknowledging you're working through a mere game (or myth?) yet simultaneously coming across as cold. (Am I alone thinking The Archetype was a jab at The Architect from The Matrix?)

'Tis a strange game, it wins you over in the end through sheer force of personality despite being riddled with gameplay problems. Like you, I don't see any theme behind the theme here, just a game that is comfortable knowing what it is.

Hah, yeah, they Archetype might be an Architect jab. Although he certainly feels less superfluous than that character…

The inevitability of what unfolds is another theme I didn't really touch upon, but that also ties into its mythic qualities.

You're right, it has a tremendous amount of personality and that sees it through – though I'd quibble on your last point there because it's not entirely upfront about what it is. I'd say it's comfortable just /being/. But then as this review makes clear I have had my wank hat firmly wedged over my ears the past few days…

So when do we get to enjoy your words on the game? :)

Oh my words "on the game" are not going to be what you'd expect and won't be as, er, revelatory as all that. Don't know when they're coming but Electron Dance schedule is blocked out until second week of September so far…

I am reminded of Kieron Gillen's piece on S&S though – about how the game really cares even though it pretends to be so aloof. That's so bang on.

Oh yeah. It has far more heart than it would like to admit. It's exuberant.

The artwork is beautiful.

It is even more gorgeous in motion.